The CSO – Chief Strategy Officer – is a relative newcomer to the C-suite. The role has quickly established itself as a formal member of the top management team or head of the central strategy department. Alongside the COO, CFO, CIO and CMO, the CSO now has a secure place among the top functions in firms across Europe.

In our extensive annual study, in cooperation with the University of St. Gallen, we examine the role of the Chief Strategy Officer in European firms. For this year’s CSO survey, we contacted the chief strategists of the 500 biggest firms in Europe. Of these, 156 agreed to take part in our survey – a response rate of 31%. Among those are CSOs from firms in German-speaking countries (Germany, Austria, Switzerland), Benelux (Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg), the Nordic countries (Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark) and Latin Europe (France, Italy, Spain, Portugal). The participating firms have an average headcount of 25,000 and most are listed on the stock exchange. This sample was then subdivided by industry, region and KPI-based performance which revealed some surprisingly clear differences with regard to strategic topics and approaches. The data we were able to gather allowed us to identify a number of success factors which form the basis for our seven statements below.

Statement 1 – The Bar has been raised

In last year’s survey, we noted that the relevance of CSOs grows in times of uncertainty, but the size of their strategy department does not grow to the same extent. Our forecast was correct: Compared to 2011, the median number of employees in the strategy department of firms in German-speaking countries (DACH) remained 7 full-time equivalents (FTE). For firms in Europe as a whole, this median was 5 FTE. If requirements are growing faster than resources, then the bar has been raised. The strategy process therefore needs to be highly efficient. CSOs must now achieve more with the same resources. This varies depending on industry and region. CSOs working for financial services companies and in the Nordic countries, for example, have seen above-average growth in both their importance and the resources at their disposal. CSOs working in retail and in the Benelux countries, by contrast, are a long way behind.

– The CSO must now achieve more with the same resources. –

Statement 2 – Knowledge and networks are key

What qualifies a CSO for his position? When it comes to personal background, CSOs have a number of things in common: They are typically younger than 50 (four out of five respondents), have a degree and a disproportionately large number of them studies at a top international university. It is clear what companies are looking for in a CSO: They want someone who is a breath of fresh air but not inexperienced. Six out of ten CSOs have gained expertise in strategy or general management in previous positions. Firms appoint people already in the firm (“insider”) and newcomers (“outsider”) in roughly equal proportions. Broadly speaking, in many industries and regions the job of CSO is a springboard for highly qualified, ambitious professionals with strong process and methodological skills. But the door is not closed to well-connected insiders. Two types of CSOs thus exist: young dynamos and seasoned old hands. Both types can be successful, but both need the right education and a good network behind them.

– Two types of CSOs thus exist: young dynamos an seasoned old hands. –

Statement 3 – Good strategists act as mediators

The traditional field of strategy formulation remains high on the CSO’s agenda, as does acting as a sounding board for the CEO or board of directors. But the clearest gains in importance in German speaking-countries, compared to the previous year, are in M&A and synergy management – areas where close cooperation with other functions is called for. Across Europe, realizing synergies is even more important. More and more, a priority task for CSOs is to create a corporate business model, leverage synergies at the firm level and optimize cross-functional processes. CSOs have the chance to become the central coordinator in the corporate headquarter, working closely with other corporate functions and operating units. CSOs appear to be in a good position to perform this coordinating, interactive role. They already see themselves as playing a leading role not just with regard to the key strategic decisions in their firm, but also in areas such as M&A and expansion into new markets. They say that they work closely and on an equal footing with the finance, marketing & sales and operations functions. Not surprising that CSOs have to continually come up with convincing arguments and demonstrate these requirements becomes a mediator between corporate functions and protector of higher interests – and thus a true strategic leader.

Statement 4 – Growth is not enough

Our results show that the most important strategic decision of the past year was mainly in portfolio management (41%), followed by growth (22%), costs (19%) and strategy implementation (16%). Once again there are interesting differences between industries and regions. Portfolio management is by far the most important topic for financial services, the industrial sector and services, while growth issues are high on the agenda for firms in retail and the life sciences. Not surprisingly, growth is also (once again this year) an important topic for firms in German-speaking

Europe and the Nordic countries, as well as for high-performing firms, while it has almost no importance at all in Latin Europe. New this year is the fact that growth and efficiency topics overall rank about the same. In other words, the traditional cycle of phases of growth followed by phases of consolidation no longer applies. The current concept is one of profitable growth through smart portfolio management and maximum efficiency gains. The new core challenge for successful organizations is ambidexterity: the ability to combine contradictory characteristics. This is perhaps the most serious conflict of objectives that today’s CSOs must manage.

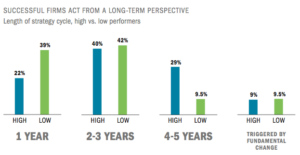

Statement 5 – Pacemaking pays off

The CSOs are in agreement that time pressure is growing and uncertainty continues unabated. That means it’s a good time for strategy – but is it a good time for CSOs too? Chief strategists have always had to be two things at once: able to take fast and decisive action while being thoughtful and aware of the risks. What is particularly important today, however, becomes clear when we compare high-performing with low-performing firms. Successful firms make bold strategic decisions from a long-term perspective. Speed is important, but is not the be-all and end-all. Most CSOs, especially those in successful firms, say that they act (and react) faster than the competition. But three out of four firms take at least three months over their most important strategic decisions. Financial services companies are above-average in terms of the speed of their decision making, while firms in the life sciences and services industry and in the consensus-oriented Nordic countries weigh up strategic decisions particularly carefully. Surprisingly, high-performing firms take longer on average to make decisions than less successful firms. Despite increasing time pressure, high performers are not so much faster when it comes to implementation as more comprehensive. Typically, a strategy cycle lasts two to three years – rather less in the industrial sector and for retailers, and rather more in the financial sector and life sciences. Low performers are more than twice as likely to have strategy cycles of less than a year – a further indication that taking a perspective of longer than a year pays off. Clearly, today’s CSOs find speed important but the avoid taking action for action’s sake.

– Most CSOs, especially those in successful firms, say that they act faster than the competition. –

Statement 6 – Conflicts are useful

The openness with which strategic discussions are carried out today, according to many CSOs, can lead to conflict or in the worst-case scenario even split the top management team. Once again, the chief strategists of financial services companies appear to be particularly active in discussing while the CSOs of retail firms and companies in the Nordic countries are more consensus-oriented. Conflicts can help expand one’s field of perception and boost creativity. However – and this seems to be the secret of success of high-performing firms – rational disputes should not be allowed to tip over into emotional conflicts or interpersonal problems. Our evaluation shows that firms which make high-quality decisions are particularly good at solving conflicts in a matter-of-fact manner, without people taking things personally. Conflict management is thus another hot-button issue where CSOs must increasingly prove their worth.

Statement 7 – Business agility is critical

The CSOs in our survey are clear Business agility will shape their agenda most going forward, meaning the ability to adapt quickly to changes in the business environment. Innovation, business model design and fast execution are also at the top of their list of priorities. At the bottom of the list come three topics that are paradoxically receiving great media attention at the moment: big data, real-time strategy and corporate social responsibility (CSR). Despite this strong move in the direction of business agility, the strategy of most CSOs is very risk-aware and rather careful. There is no clear appetite for risk except in the financial sector. Indeed, quite the opposite: CSOs prefer to act slowly and approve project step-by-step. The bottom line is that strategy must strengthen business agility without taking unnecessary risks. Here, again, CSOs must resolve a conflict of objectives and achieve the right balance.

The seven statements above show that today’s firms need a new type of strategic leadership. This is the core message of our study in 2013. The informal, get-up-and-go CSO of yesterday no longer fits the bill: What firms need is a carefully calculating, thoughtful, mediating CSO with a cross-functional, interdisciplinary mindset who nevertheless can make decisions fast and implement them effectively. As the title of our study puts it: CSOs have to be the “Masters of paradoxes”.

This article is based on the study report „Menz, M., Scheef, C., Müller-Stewens, G., Zimmermann, T., Lattwein, C., & Lang, A. 2013. Masters of Paradoxes, Key Findings of the Chief Strategy Officer Survey 2013. St. Gallen/Munich. University of St. Gallen/Roland Berger Strategy Consultants.